This is Part 3.1 of a series of posts on the construction of a diorama depicting the Zeros of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Akagi aircraft carrier preparing to take off as part of the first wave attack on Pearl Harbor. This post only concerns Masanobu Ibusuki. To understand the concept of this diorama project, please refer to this post. To view the finished diorama, please click here.

As mentioned in the preceding post, the Japanese pilots who participated in the Pearl Harbor attack were considered some of the most experienced, most highly skilled, and best-trained pilots in the world at the outbreak of the Pacific War. Still, their odds of surviving the war were minimal, irrespective of experience, skill, or training. As previously discussed, only two of the nine pilots survived the war. One of these was Masanobu Ibusuki, whose post-war story I found compelling.

As with Shigeru Itaya, I could find no biography of Ibusuki in any book or on the internet. What follows is derived from one-sentence references in various books as well as bits and pieces from obscure corners of the internet.

Assigned to the IJN’s Flagship Akagi

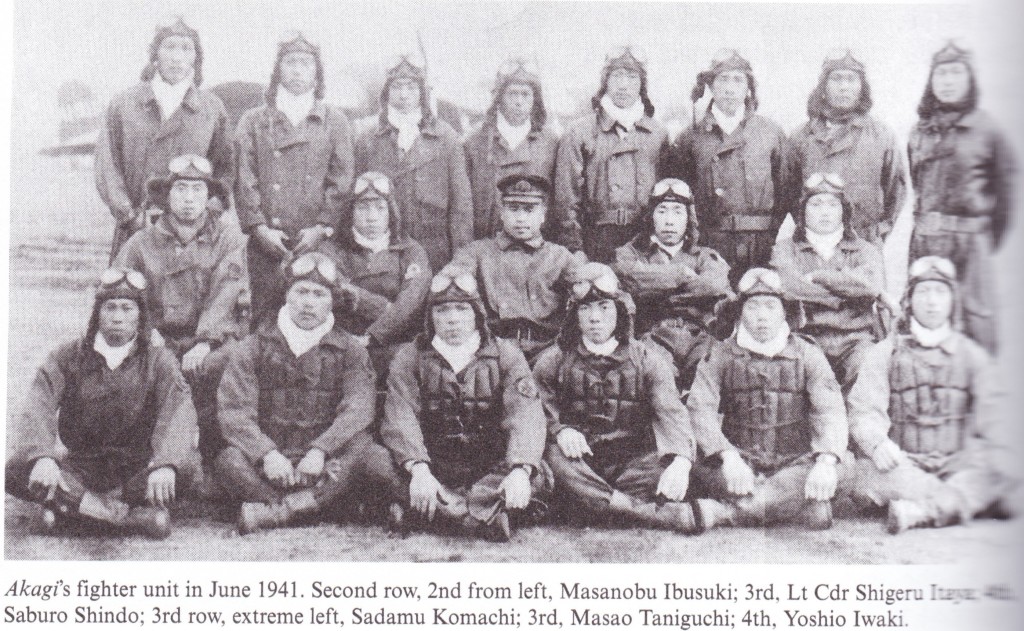

Ibusuki graduated from the Japanese Naval Academy in April 1940 and joined the fleet as a lieutenant in March 1941, less than a year later. He was assigned to the Akagi as a Zero fighter pilot and by early October was training for Pearl Harbor at Kagoshima Harbor, a Japanese harbor with similar terrain. Below is a photo of Akagi’s fighter pilots taken six months before Pearl Harbor (Japanese Naval Fighter Aces 1932-45, Ikuhiko Hata et al).

Attack on Pearl Harbor

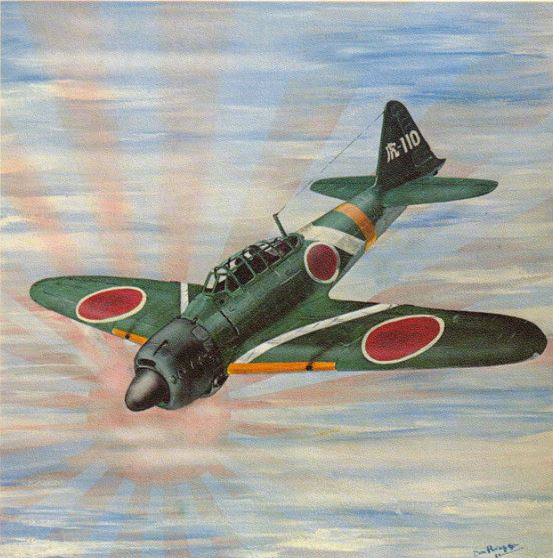

At Pearl Harbor, Ibusuki was second in command to Shigeru Itaya, leading the second Shotai of Akagi Zeros in the first wave. His primary mission was to intercept American resistance above Pearl Harbor; his secondary mission was to strafe battleships anchored at Ford Island and parked aircraft at Hickam Air Field. The box art below from Trumpeter’s 1/24 scale Zero kit shows Ibusuki’s aircraft (AI-103) at Pearl Harbor. The two yellow stripes on the tail designate him as chutai (squadron) leader of the nine Akagi aircraft in the first wave.

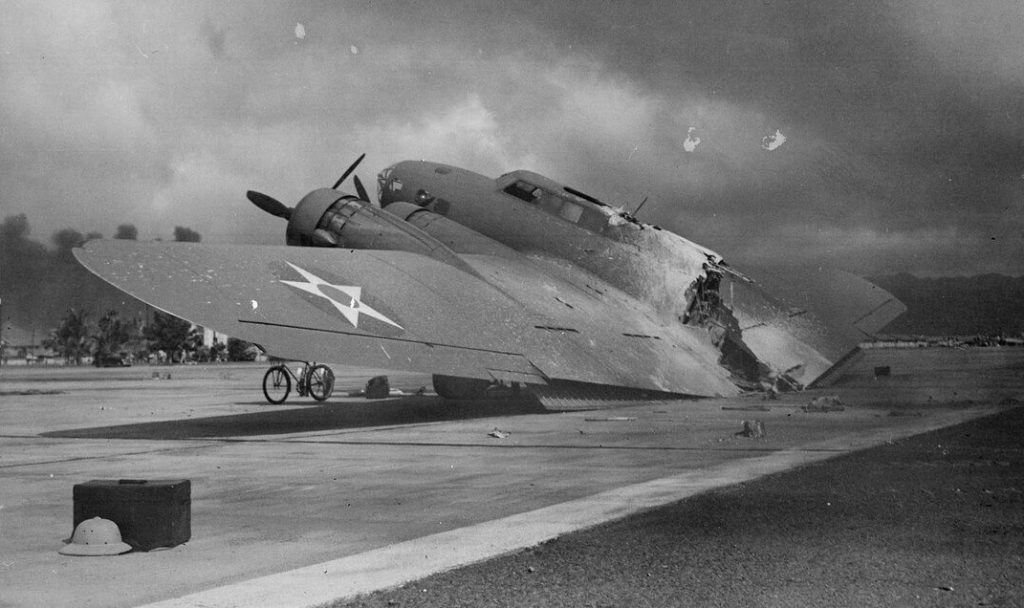

Along with Itaya, Ibusuki was one of two Zero pilots credited with shooting down Captain Raymond Swenson’s B-17 (#40-2074) Flying Fortress at Hickam Air Field – the first B-17 casualty of the war. The public domain photo below shows what was left of the B-17 (Pearl Harbor Visitors Bureau website). The panoramic photo below was created by friend and fellow hobbyist Ara Hagopian by merging and enhancing three separate screen captures from color film taken by Sgt. Harold Oberg just three hours after the attack. The wreckage of the B-17’s fuselage can be seen on the far left. The severed tail can be seen on the far right of the photo.

The panoramic photo below was created by friend and fellow hobbyist Ara Hagopian by merging and enhancing three separate screen captures from color film taken by Sgt. Harold Oberg just three hours after the attack. The wreckage of the B-17’s fuselage can be seen on the far left. The severed tail can be seen on the far right of the photo. Raids on Port Darwin and Colombo

Raids on Port Darwin and Colombo

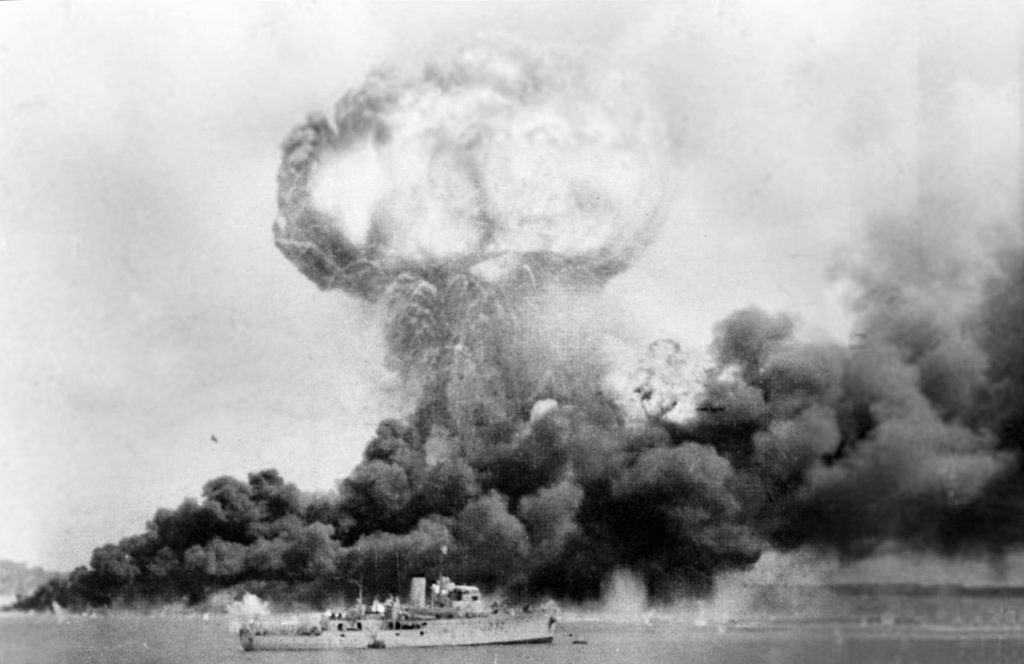

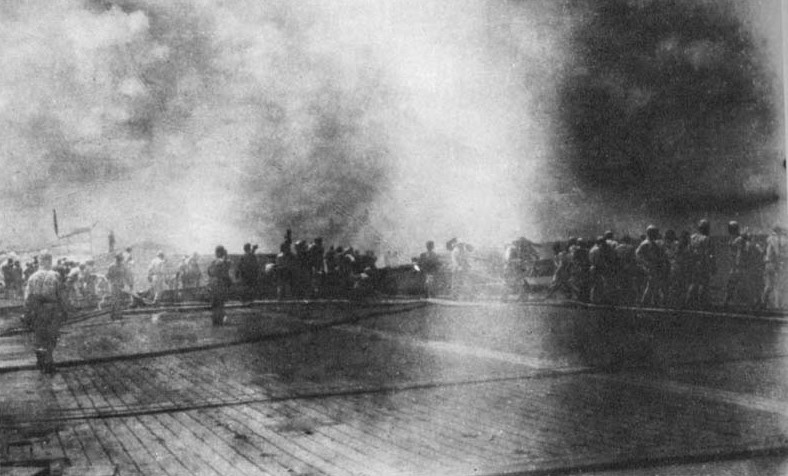

Ibusuki participated in numerous attacks on allied ports and ships while assigned to the Akagi. In February 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor, he participated in the raid on Port Darwin, Australia and in April 1942 in the raid on Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) – two Japanese attacks on British ports that were virtually identical in scope and execution to the attack on Pearl Harbor. The photo below shows Australian ships burning at Darwin Harbor after the attack (Wikipedia MV Neptuna entry).  Cheating Death at Midway

Cheating Death at Midway

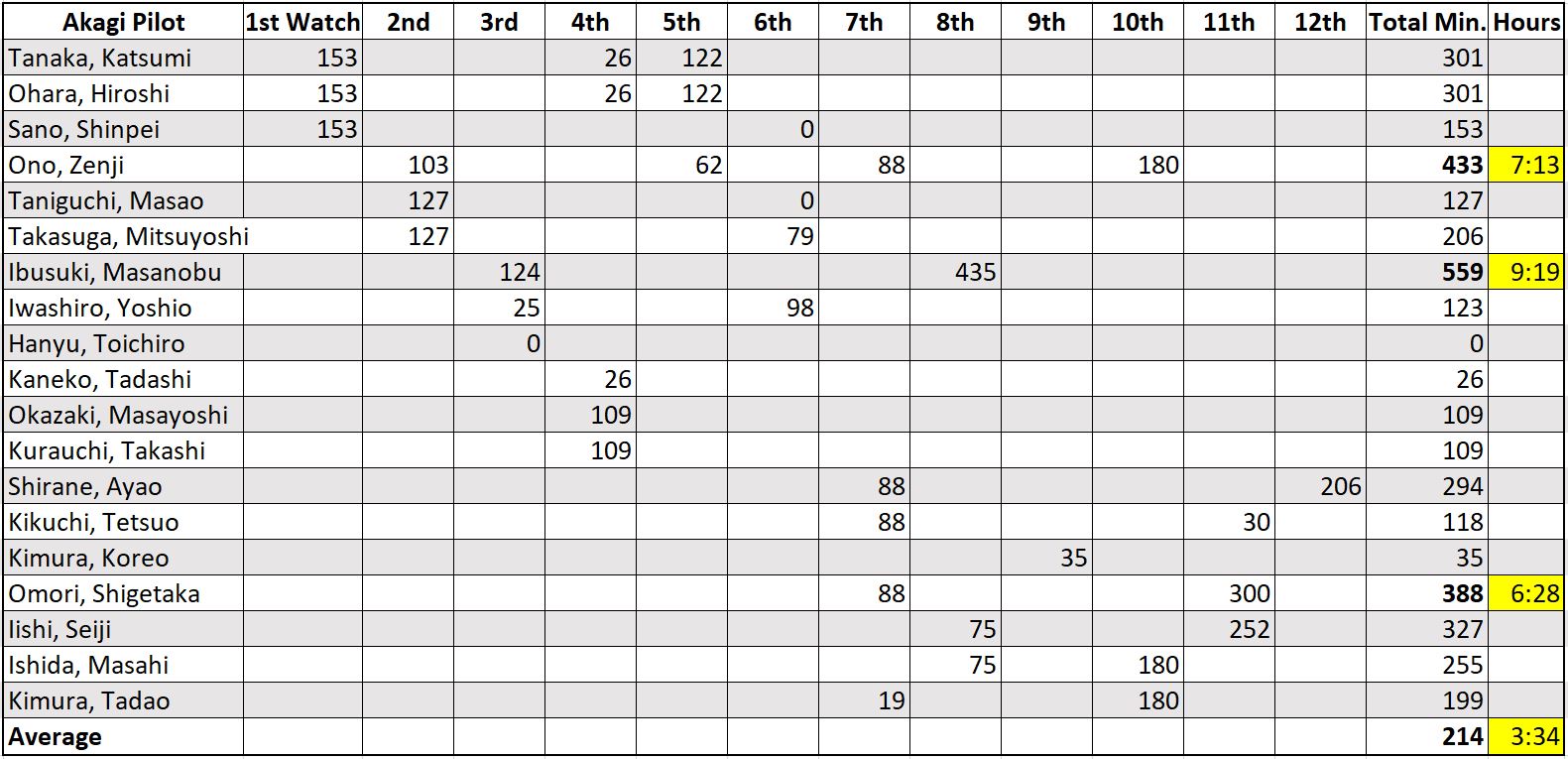

Probably more than at any time during the war, Ibusuki showed his mettle on June 4, 1942 at the Battle of Midway. While the entire Combat Air Patrol (CAP) — the Zero fighters charged with patrolling overhead to protect the Japanese fleet — worked extraordinarily hard throughout the battle, no one worked harder than Masanobu Ibusuki. Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway, Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully’s outstanding 600-page tome on Midway, includes Japanese operational records from the carrier air groups. The data shows when each CAP watch group launched and when it returned, as well as the pilots who comprised each group.

I gleefully added the periods each Akagi pilot was in the air during the various watches and produced the table below. As the table demonstrates, Ibusuki participated in two watches: the Third for 2 hours and 4 minutes; and the Eighth for 7 hours and 15 minutes, totaling 9 hours and 19 minutes patrolling overhead. The pilot with the next highest time, Zenji Ono, spent a total of 7 hours and 13 minutes during four watches. It bears mentioning that the average flight duration for all 19 Akagi pilots was 2 hours and 34 minutes — roughly a third of Ibusuki’s time. While I did not tabulate the periods for the pilots of the three other Japanese carriers at Midway, a review of the data revealed that no pilot even came close. Ibusuki showed his commitment and love of country that fateful day as he fought off American fighters and bombers hour after hour.

Ibusuki launched for his second watch at 9:45 a.m. that morning. Merely an hour later, fires raged uncontrollably throughout the Akagi deck after SBD Dauntless dive bombers from the USS Enterprise led by Richard Best hit it with 1,000-lb. bombs. Ibusuki continued to fight for another six hours before exhausting his fuel and being forced to ditch his Zero in the ocean as he could no longer land on the burning Akagi. Like several other Akagi Zero pilots at Midway, Ibusuki was rescued by the light cruiser Nagara. The Battle of Midway decimated the Imperial Japanese Navy but Ibusuki and several others cheated death that day. The photo below from Midway 1942: Turning Point in the Pacific, by Mark Stille, shows Japanese survivors of the Hiryu, rescued by a U.S. ship after drifting 14 days — their despair is an apt metaphor for the Battle of Midway. (NB: Corgi [PR99405] produced a lovely 1/72 scale limited edition of Best’s SBD-3 Dauntless with Midway markings.)

Unscathed After Crash-Landing at Guadalcanal

The Akagi now sunk, Ibusuki was transferred in July 1942 to the Shokaku, another carrier that had been present at Pearl Harbor. In early September, during fighting at Guadalcanal, Ibusuki’s Zero’s fuel tanks were ripped by enemy fire. Out of fuel, he was forced to crash-land just off-shore, in an area controlled by the Japanese. Again, he survived unscathed and was soon back in action.

A few months later, in October 1942, he led 20 Zero fighters at the Battle of Santa Cruz. Though the Shokaku was severely damaged from three direct hits, requiring it to return to Japan for repairs, it did not sink, yet it counted a meager four surviving Zeros by the end of the battle. Ibusuki had survived yet another close call. The photo below shows the crew of the Shokaku fighting fires on the flight deck during the battle of Santa Cruz (Wikipedia Shokaku entry).

Surviving the “Turkey Shoot” with the “Tora” Unit

As the Shokaku underwent repairs until February 1943, its experienced pilots were reassigned to other carriers and land-based units. While it is unclear where Ibusuki was assigned during the Shokaku’s repairs, by June 1943 he was serving as group leader of the newly formed land-based Air Group 261 — the Tora (“Tiger”) unit — at Kagoshima. The cover illustration below, from Japanese Naval Air Force Camouflage and Markings, Donald W. Thorpe’s seminal work on Japanese markings, could well be Ibusuki’s aircraft. Without mentioning Ibusuki, Thorpe describes the Zero in the illustration (虎-110) as belonging to the Group Leader of Air Group 261; on the other hand, without referencing this specific Zero, Hata names Ibusuki as the Group Leader of Air Group 261. It is reasonable to conclude from these two references that this might be Ibusuki’s aircraft since his membership covered the entire life of the Tora unit. (NB: Both Dragon [50049] and Witty [72-012-005] have produced 1/72 scale models of 虎-110.)

In June 1944, Air Group 261 suffered heavy losses during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the largest carrier-to-carrier battle of the war. The aerial part of the battle came to be known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot because of the disproportionate losses suffered by the Japanese — over 600 aircraft were lost versus only 123 lost American aircraft.  The photo at left is a graphic symbol of the destruction suffered by the IJN. While Ibusuki survived the battle, his unit was decimated. In July 1944, only a month after the Turkey Shoot, Air Group 261 was disbanded and what remained of its personnel was reassigned to Air Group 201, yet another prestigious land-based fighter unit operating out of the Philippines.

The photo at left is a graphic symbol of the destruction suffered by the IJN. While Ibusuki survived the battle, his unit was decimated. In July 1944, only a month after the Turkey Shoot, Air Group 261 was disbanded and what remained of its personnel was reassigned to Air Group 201, yet another prestigious land-based fighter unit operating out of the Philippines.

Surviving the First Kamikaze Unit

Barely three months later, Ibusuki was involved in one of the most controversial decisions of the war. Amid continued Japanese losses and distressed by the inexorable American march to his homeland, Takijiro Onishi, the Admiral in charge of the First Fleet under which Air Group 201 operated, reluctantly concluded that special attack suicide units willing to crash their explosives-laden aircraft into Allied vessels would be more effective than conventional bombing in slowing the rapidly advancing American forces. On October 19, 1944, Onishi consulted with Air Group 201 leadership, including Ibusuki, regarding the creation of such a unit. Cognizant of the Emperor’s Rescript requiring subjects to carry out their duty at any cost, Ibusuki assented. Onishi, now known as “father of the Kamikaze,” thus ordered Air Group 201 to form the first Kamikaze special attack unit. As the special attack units met with some success, the tactic spread throughout the IJN as the war reached its inevitable conclusion. Of the estimated 3,800 Kamikaze pilots who sacrificed their lives in these deliberate suicide attacks, more than 200 belonged to Air Group 201. In January 1945, surviving Air Group 201 pilots, including Ibusuki, were transferred to Taiwan.

Finishing the War with the Yokosuka Kokutai

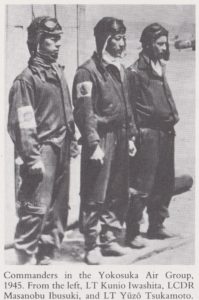

Whereas most Air Group 201 pilots lost their lives, Ibusuki again survived, ultimately joining possibly the most elite unit of the Japanese Imperial Navy — the Yokosuka Kokutai. Created in 1916 as an aircraft testing and research unit, and to develop aerial fighting techniques, the Yoko Ku, as it came to be known, attracted the cream of Japanese pilots from all armed forces. In February 1944, as the IJN became desperate for pilots following Japanese heavy losses, the Yoko Ku was forced to become a fighting unit. Ibusuki must have joined the Yoko Ku in early 1945, after Air Group 201 was dissolved. According to Hata, in mid-February 1945, a group of 10 Zeros, Shiden-Kai, and Raiden aircraft led by Ibusuki shot down 19 American F6Fs and F4Us operating from aircraft carriers over Atsugi, Japan, about 25 miles southwest of Tokyo. The photo at left from Ikuhiko Hata et al’s Japanese Naval Fighter Aces shows Ibusuki while with the Yoko Ku.

In February 1944, as the IJN became desperate for pilots following Japanese heavy losses, the Yoko Ku was forced to become a fighting unit. Ibusuki must have joined the Yoko Ku in early 1945, after Air Group 201 was dissolved. According to Hata, in mid-February 1945, a group of 10 Zeros, Shiden-Kai, and Raiden aircraft led by Ibusuki shot down 19 American F6Fs and F4Us operating from aircraft carriers over Atsugi, Japan, about 25 miles southwest of Tokyo. The photo at left from Ikuhiko Hata et al’s Japanese Naval Fighter Aces shows Ibusuki while with the Yoko Ku.

The last Ibusuki wartime reference I could find was from August 1945. Following Japan’s unconditional surrender, American B-29s were spotted flying over Japan contrary to the terms of the ceasefire. Eager to intercept the American bombers, his men turned to now-commander Ibusuki for guidance. “International law forbids us to attack the enemy after surrender, but it is okay to get back at planes that attack us. Come on men, go get [them],” Ibusuki responded. Ibusuki’s WWII service was thus book-ended by the beginning of the Pacific conflict at Pearl Harbor and by its conclusion with the Japanese surrender.

The few paragraphs above are the sum total of what I could cobble together regarding Ibusuki’s wartime service from the score of brief one-sentence references to him in a couple dozen books at several libraries. Having concluded definitively that Ibusuki had survived the war, I began searching in post-WWII sources. My persistence was soon rewarded.

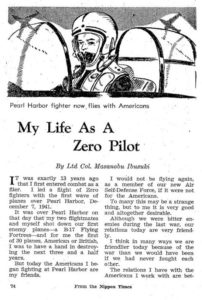

Ibusuki in His Own Words

I eventually found a reference to an article Ibusuki had written in 1955 for the English-language Nippon Times (now Japan Times) entitled “My Life as a Zero Pilot.” Lacking access to the Nippon Times, I learned that the article had been reproduced in a little-known journal called Japan Digest. Unfortunately, the digest was nowhere to be found online and only a handful of libraries in the U.S. carried the hard copy. I wrote to Indiana University Library and, after paying a fee and waiting a few days for someone to scan it, received a three-page PDF file by email.

At long last here was Ibusuki, telling his story in his own words – in English no less! While copyright laws prevent me from posting the entire article, these are the most salient points: Ibusuki had participated in some of the most intense episodes of the war, including Pearl Harbor, Port Darwin, Colombo, Midway, Rabaul, Saipan, and other Pacific battles. “I was not afraid – as I recollect – but I doubted that I would survive the war,” Ibusuki muses of Pearl Harbor. But he had indeed survived the war and was fortunate not to have been wounded, particularly as he had participated in the bloodiest fighting of the war. However, he had several brushes with death, including once ditching his plane at Midway, as previously discussed, and twice crash-landing after suffering battle damage at Guadalcanal and Peleliu. As I had surmised, he had indeed made ace – six times over – having shot down 30 planes (25 American and five British) during the war, including five in just one battle off the coast of Ceylon (two Hurricanes, two Spitfires, and a Swordfish torpedo bomber), according to his account.

But he had indeed survived the war and was fortunate not to have been wounded, particularly as he had participated in the bloodiest fighting of the war. However, he had several brushes with death, including once ditching his plane at Midway, as previously discussed, and twice crash-landing after suffering battle damage at Guadalcanal and Peleliu. As I had surmised, he had indeed made ace – six times over – having shot down 30 planes (25 American and five British) during the war, including five in just one battle off the coast of Ceylon (two Hurricanes, two Spitfires, and a Swordfish torpedo bomber), according to his account.

Joining the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force

Ibusuki had joined the National Safety Force formed by Japan with American aid in 1952. In 1955, now nearly 40 years of age, he had learned English and was a member of Japan’s newly formed Air Self-Defense Force, which replaced the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy (the non-bellicose name complied with a provision in the new Japanese Constitution that Japan may not maintain war-making potential). Ironically, Ibusuki was flying U.S.-donated F-86 Sabre Jets (the American response to the Soviet MiG-15) and being trained by U.S. instructors. According to some sources, there were 30 applications for every opening and recruits were required to have a university education and proficiency in English. Ibusuki had nothing but praise for his American trainers and was pleased to be sitting in the cockpit once more. “I have won my wings again, and I am flying once again,” Ibusuki declares in closing. The photo below shows F-86 Sabres of the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force (Asian-Defence-News.blogspot.com July 2015). Encouraged by the Japan Digest article, and armed with more information, it became easier to locate additional articles. In March 1956, several U.S. dailies carried a brief article, similar to the one below from the San Rafael Daily Independent Journal dated March 1, 1956, detailing Ibusuki’s participation in joint U.S.-Japan training exercises in Japan. (The article is brief and mostly factual, and I felt comfortable posting it under the theory that facts cannot be copyrighted.)

Encouraged by the Japan Digest article, and armed with more information, it became easier to locate additional articles. In March 1956, several U.S. dailies carried a brief article, similar to the one below from the San Rafael Daily Independent Journal dated March 1, 1956, detailing Ibusuki’s participation in joint U.S.-Japan training exercises in Japan. (The article is brief and mostly factual, and I felt comfortable posting it under the theory that facts cannot be copyrighted.)

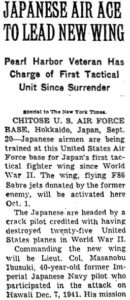

Further research yielded several other 1956 articles that referenced Ibusuki in connection with the formation of Japan’s first tactical fighter wing since WWII. The most important of these was a September 1956 New York Times article entitled “Japanese Air Ace to Lead New Wing.” The article is noteworthy because of its unequivocal reference to Ibusuki as an “ace” with 25 victories over U.S. aircraft. The article details the creation of the Air Self-Defense Force and, among other things, describes how Ibusuki was a favorite of American pilots at the officer’s club. The first part of the article appears at right. Copyright laws prevent me from posting the entire article.

The article is noteworthy because of its unequivocal reference to Ibusuki as an “ace” with 25 victories over U.S. aircraft. The article details the creation of the Air Self-Defense Force and, among other things, describes how Ibusuki was a favorite of American pilots at the officer’s club. The first part of the article appears at right. Copyright laws prevent me from posting the entire article.

Nearly Cheating Death Again

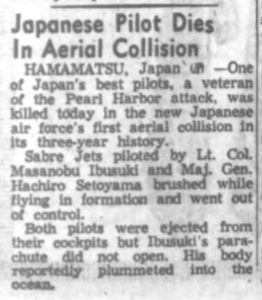

However, less than four months later, the 41-year-old Ibusuki was dead. On January 9-10, 1957, just over 15 years after Pearl Harbor, several U.S. newspapers carried variations of the blurb below — this one from the Arizona Republic dated January 10, 1957:

Japanese Jet Pilot Dies in Air Collision TOKYO, Thursday (INS) – Japan lost one of its leading jet pilots yesterday when Lt. Col. Masanobu Ibusuki, 41, was killed in a collision between two American-built F-86 Sabrejets of the Japanese Air Defense Force. The pilot of the second plane, Maj. Gen. Hachiro Setoyama, commander of Japan’s Second Air Wing, parachuted to safety (emphasis mine).

Another brief article from January 9, 1957, in the Jamestown (N.Y.) Post-Journal provided additional information:

Japanese Pilot Dies in Aerial Collision HAMAMATSU, Japan (IP) – One of Japan’s best pilots, a veteran of the Pearl Harbor attack, was killed today in the new Japanese air force’s first aerial collision in its three-year history. Sabre Jets piloted by Lt. Col. Masanobi Ibusuki and Maj. Gen. Hachiro Setoyama brushed while flying in formation and went out of control. Both pilots were ejected from their cockpits but Ibusuki’s parachute did not open. His body reportedly plummeted into the ocean (emphasis mine).

Setoyama, himself a navy bomber pilot during WWII, parachuted to safety. Ibusuki, who had repeatedly cheated death during the war, actually survived the collision and successfully ejected from the Sabre. Ultimately, however, he was unable to cheat his destiny when his parachute failed to open. The sea, over which he flew his entire career as a naval pilot, made good its claim over him – perhaps fittingly . If death was unavoidable, Ibusuki could not have chosen a more suitable end, particularly given his dedication to duty as a Japanese pilot steeped in the Code of Bushido – “always prepared to die.”

. If death was unavoidable, Ibusuki could not have chosen a more suitable end, particularly given his dedication to duty as a Japanese pilot steeped in the Code of Bushido – “always prepared to die.”

The Unsung Ace

Ibusuki’s own article, published in the Nippon Times, where anyone could have contested his assertions, the New York Times article, which holds itself to the most stringent fact-checking standards, as well as many other short articles from various newspapers, invariably either credit Ibusuki with 25-30 kills, or otherwise refer to him as an “ace.” Why then does Ibusuki not appear on available lists of aces, such as Ikuhiko Hata et al’s Japanese Naval Fighter Aces 1932-45 (1989) or Henry Sakaida’s Imperial Japanese Navy Aces 1937-1945 (1998)? Ibusuki’s situation is similar to Itaya’s, an issue covered in a previous post. It is simply inconceivable that any pilot could survive four years of constant “kill-or-be-killed” aerial combat in WWII, including nine hours of fighting at Midway, without achieving five victories. The logical and inescapable conclusion is that the lists are incomplete, at least with regard to Ibusuki. If anyone reading this post has access to Henry Sakaida, one of the foremost experts on Japanese aces of WWII, please refer him to this post. Perhaps the record can be set straight — if indeed it is incorrect — and Ibusuki can claim his rightful place in Japanese naval history.

Thank you for your indulgence and I hope you enjoyed the post or at least found it informative. If something looks amiss, please let me know. I would be delighted to correct inaccurate information so that this may be useful to other 1/72 scale collectors and wargamers. As always, comments, questions, corrections, and observations are welcome. As mentioned, stay tuned for an overview of IJN pilots available in 1/72 scale in the next post.

I’d like to thank the great folks at Indiana University Library for their courteous and quick service in locating, scanning, and sending me Ibusuki’s article. I would also like to remind readers that I’m merely a 1/72 scale plane, tank, and soldier collector — not an academic or expert on this subject by any means.

Lagniappe Paragraph: “Life Imitates Art Far More than Art Imitates Life”

I realize this is totally off-topic, but as I avidly read about Ibusuki’s death, my thoughts drifted to the eerie similarities with the backstory of Bartholomew Quint, the ill-mannered professional shark hunter in Spielberg’s 1975 blockbuster movie Jaws. Serving on the USS Indianapolis, which had just delivered “Little Boy” to Tinian to be used on Hiroshima, Quint was one of just over 300 out of 1,200 men who survived its sinking by a Japanese submarine torpedo on July 30, 1945 – literally 16 days before the Japanese surrender. Approximately 900 men survived the sinking itself; of those, almost six hundred perished over the next four days from dehydration, salt-water poisoning and, more importantly for this article, shark attacks. Quint, who had been traumatized after witnessing many of his shipmates being eaten by sharks, ironically met his fate in the same terrifying manner – only thirty years later. Like Ibusuki, Quint eluded his fate during the war – but it was merely a reprieve.

For anyone interested in Robert Shaw’s unforgettable performance as Quint, particularly as he recounts the sinking of the Indianapolis, below is a four-minute YouTube video. Please note that Quint’s dates and figures are slightly inaccurate.

Bernd Hartwig says:

Thank you for such an outstanding piece of research! I´ve just read your article with great pleasure. I just came to this website through a Google pics search on a Dragon model that I’m considering buying. Like you, I like to know a bit about the models I own (but my knowledge is far less profound than yours).

I collect 1/72 WW2 fighter models that I display in pairs. As I´m quite clumsy, I restrict myself to preassembled diecast models. I started with a few Oxford diecast pairs in late 2018 before finding out that the models sometimes don´t match at all. Since then I try to put together models that at least flew during the same timeframe and region. It´s quite interesting for me to find an adversary for a given model, I learned a lot about WW2 air combat by researching a model´s background.

So thank you very much for providing me with such profound information!

Best regards,

Bernd Hartwig